Why is it that I am always late when I drop by the Frick Gallery in Manhattan? And after plowing through the Fragonards, stopping respectfully at the Goya, and practically running down the dark green museum hall, where I don’t remember the paintings because I am so annoyed that I will never own a house with a hall dedicated to art I love, why is it that I always come to a grinding halt before a small modest Manet and I begin to worship like a Muslim, who at the call of the muezzin stops what he is doing, unrolls his pray mat, and talks to god.

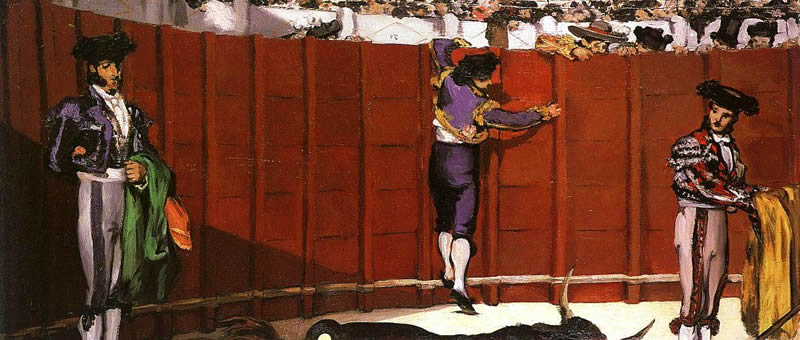

It happens every time and not just to me. I tell my girlfriend, Victoria, and without letting me finish she replies, “Oh yes, the little Manet, I can never pass it by.” It’s a painting of bullfighters in the ring, but it is not dramatic, on the contrary, it is almost intimate and yet it is impressive, dominating the rest of the room. One begins to suspect it of holding a terrible secret but in fact it seems rather simple and straight-forward.

What is it about this painting? My eyes search the dark velvet shadow of the wall, the white hot glistening sand of the ring, the matador’s beautiful black shoes, ballet slippers made for dancing not the slaughtering of animals, and his pink tights made for women not for men. Two bullfighters are caught off-guard as another toreador turns to run, while the Bull is glimpsed like a playful snake along the bottom of the painting (We only see his tail, the top of his back, and his head and horns).

But something else is there too, hiding in the hush of the painting. This painting has frozen the one thing I have yet to grasp, the present, the moment before words try to solidify what has already been felt, that piece of sunlight that stops you in your tracks as if you had never seen sunlight before and will never see it again, in other words, life before death takes it back… or has death already stepped into the ring.

The puzzle did not drop into place until I learned that Manet had actually cut the original canvas in half, (which is why, I suppose, most of the bull is out of the picture). The other half of the canvas is called Dead Toreador and he lies on the sand in a different gallery altogether, while our painting hangs on the wall of the Frick in a constant state of loss. You cannot cut the heart out of a painting. Unlike a human it does not die – it goes on silently searching for its missing piece.

Manet has captured a moment, a precious piece of time but it is the moment after death, not before. The elegant stillness of the little painting at the Frick is the silent entrance and exit of death, the cold horror that cuts through even the brightest sun light. The casual poses are of people in shock. The bull’s feet dance out of frame like the devil, while like any other eviscerated animal, our painting can only wait helplessly for the return of its heart.

Artillery Magazine Vol 1 no. 4 March 2007