Here’s to LACMA for giving us one of the most essential shows of the decade. Usually I go to judge art, this time I was there to learn. How would you feel if in every mirror you did not recognize yourself because the image you saw was dreamed up by some man, and your job was to live up to it? The mirrors I am talking about were paintings and most artists were men. Until Surrealism, that is. Suddenly dreams, illusions and unspoken feelings appeared on canvas, breaking the restrictions of logic and unsealing the creativity of women, because this was her language, the language of a shut in, trapped in her mind without a voice, language that sometimes found its voice in a crazy quilt or a piece of lopsided pastry. But now the muse began to paint, recognizing the surrealist symbols in a deeper way than her male counterpart as markers along a path to regain her voice and turn her image back into human form. “In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States” details the dramatic measures these women adopted and the lonely paths they followed in order to shatter the male mirror and climb back into their own beautiful skins.

My three favorite artists in the show – Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Dorothea Tanning – all began as muses to famous surrealists. These three witches of great beauty had no interest in entering man’s realm and painting like him. Rather than inventing a new style, they looked to the discarded past, using the symbols of Alchemy instead of psychiatry. They took the feminist beliefs of the Gnostic religion, a heresy the pope murdered at Montsegur. They revived the dark power of fairytales and gave images to the nightmares of the unconscious. Instead of throwing it all in a witch’s caldron, they put it on canvass and created their image as they felt it. Almost every painting in the show is about the female figure with one big difference: it’s not for sex, it’s for her.

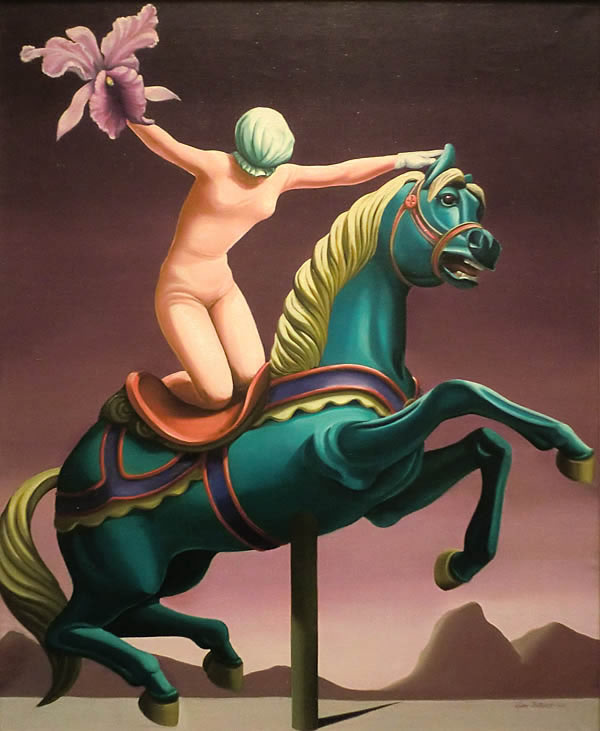

The painting, Hollywood Success by Dorr Bothwell, is not a personal exploration of a woman’s physic garden; rather, it’s a feminine comment on being a star. It’s a painting of a woman holding a large orchid and riding a horse through a very unreal landscape. Her head, masked executioner’s style, marks the necessary death of her individuality. Her hand, wearing the glove of Manners, restrains any action of her own. The individuality of her body is masked so it can be made to fit the silver screen’s idea of perfection. In imposing such model for women, the industry, not the actress, decides such details (while movies like Bridesmaids make morons out of all of us).

Of course our actress is not on a real horse but a merry-go-round career mechanically run by the industry and she will be dumped after the appropriate cycle is finished with her. Even her positioning is precarious, as she is not exactly in the saddle (in control) but poised precariously in the old begging – or blowjob – position. The orchid, which she holds high, is not the Oscar; it represents sex and it is beautiful. It is the one thing of her own that she has to give and it is the one and only thing they really want from her. This is her power.

Artillery Magazine Vol 6 no. 6 Summer 2012