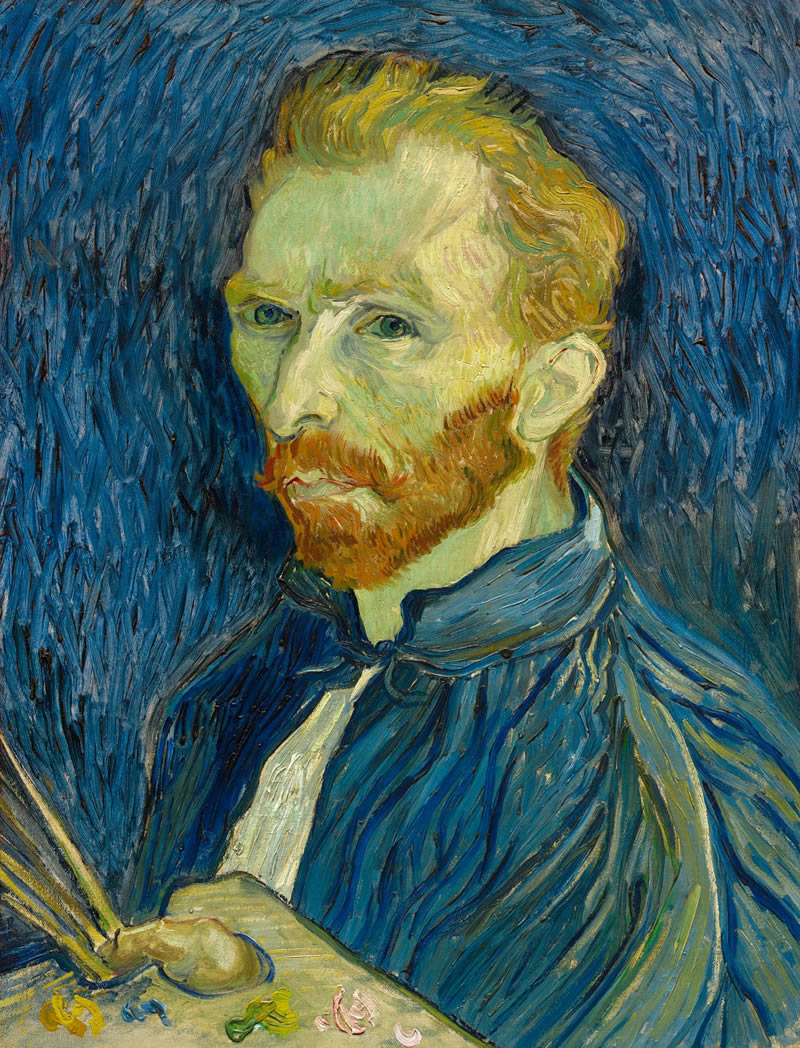

The first time I saw Vincent Van Gogh’s self portrait it was in my mother’s bedroom, hanging on the wall opposite the two Gauguins that hung over her bed. I liked the two Gauguins—they seemed happy and far away—but the Van Gogh was problematic. He didn’t look like a nice man and I was only six. Years later I understood that these were photographic reproductions that she had framed and I was embarrassed that we didn’t have real paintings like other people did. Not only that but I was told the subject matter, Mr. Van Gogh himself, was insane so that besides not liking him, now I had to feel sorry for the poor guy, trapped as he was in my mom’s bedroom, where the large blue bird pattern of the curtains and the bedspread flew endlessly around the room, making him even more crazy than he already was.

Perhaps it was his helplessness that got to me. How else can I explain my relationship to this man I never knew, confess to you that I apologized to him daily for the predicament he found himself in. Looking at his unhappy eyes and greenish face over the years I knew this thin little man didn’t want to hang around, while my crazy family watched Gunsmoke. I didn’t want to be there either, watching my family watch Gunsmoke. As high school dwindled on, V.G. and I became close pals. He would keep watch while I combed the fifties bedroom of my often hysterical mother looking for the left over pills that Daddy Doctor had put her on. We had conversations, V.G. and I—why not? He was nuts and I was strung out, maybe we were both nuts, or he was really me, or whatever.

I promised V.G. I’d take him to college with me, save him from the angry Blue Birds that reeked of Camel cigarette smoke. But of course I didn’t. Eventually I had to turn away and leave him there, which makes me want to cry, which is insane because I am seventy years old and standing in the Norton Simon Museum looking once again at Van Gogh’s piercingly unhappy eyes and familiar greenish face, now in the flesh. It’s like greeting an old friend that I had only been allowed to talk to on the phone and now I can see him face to face. I cannot look away from his eyes. They draw you down into his world, where all the lines of paint were marks and scratches made by a soul, lost in another darker place. It’s as if he can see but cannot not be heard. Suddenly it strikes me—the ability of this artist to trap so much life in a pile of dead paint on a lifeless canvas—it makes me wonder for the first time if a God really could form a man out of dead clay.

So I am no longer embarrassed that my mom hung reproductions on the wall—after all, she had enough Campbell Soup cans in the kitchen and they were the real thing.

Artillery Magazine Vol 7 Issue 4 Mar-Apr 2013